Wittenoom is a declared contaminated site and former townsite 1,420 kilometres (687 mi) north-north-east of Perth in the Hamersley Range in the Pilbara region of Western Australia.

The area around Wittenoom was mainly pastoral until the 1930s when mining for blue asbestos began in the area. By 1939, major mining began in Yampire Gorge, which was subsequently closed in 1943 when mining began in Wittenoom Gorge. In 1947 a company town was built, and by the 1950s it was Pilbara’s largest town. During the 1950s and early 1960s Wittenoom was Australia’s only supplier of blue asbestos. The mine was shut down in 1966 due to unprofitability and growing health concerns from asbestos mining in the area.

Today, three residents still live in the town, which receives no government services. In December 2006, the Government of Western Australia announced that the town’s official status would be removed, and in June 2007, Jon Ford, the Minister for Regional Development, announced that the townsite had officially been degazetted. The town’s name was removed from official maps and road signs and the Shire of Ashburton is able to close roads that lead to contaminated areas.

The Wittenoom steering committee met in April 2013 to finalise closure of the town, limit access to the area and raise awareness of the risks. Details of how that would be achieved were to be determined but it would likely necessitate removing the town’s remaining residents, converting freehold land to crown land, demolishing houses and closing or rerouting roads. By 2015 six residents remained; in 2017 the number dropped to four and to three in 2018.

Wittenoom was named by Lang Hancock after Frank Wittenoom, his partner in the nearby Mulga Downs Station. The land around Wittenoom was originally settled by Wittenoom’s brother, politician Sir Edward Horne Wittenoom. By the late 1940s there were calls for a government townsite near the mine, and the Mines Department recommended it be named Wittenoom, advising that adoption of this name was strongly urged by the local people. The name was approved in 1948, but it was not until 2 May 1950 that the townsite was officially gazetted. In 1951 the name was changed to Wittenoom Gorge at the request of the mining company, and in 1974 it was changed back to Wittenoom. The mine closed in 1966, and the townsite was officially abolished by gazettal in March 2007.

In 1968 Wittenoom was one of only two Catholic parishes in the Pilbara.

In 1917 the Mines Department first recorded the presence of blue asbestos in the Hamersley Ranges. Langley Hancock discovered Wittenoom Gorge on the Mulga Downs property in the early 1930s. In 1937 Langley (Lang) Hancock showed samples of blue asbestos crocidolite that he had picked-up in the Gorge to Islwyn (Izzy) Walters and Walter (Len) Leonard who were at that time mining and treating white asbestos at Nunyerrie and at Lionel near Nullagine. When Hancock learned the fibre would fetch £70 per ton he immediately pegged the best claims in Wittenoom Gorge. Leo Snell, a Kangaroo shooter on Mulga Downs pegged a claim on Yampire Gorge, where there was a lot more blue asbestos. Walters and Leonard purchased Yampire Gorge from Snell and moved their treatment plant there and began mining and treating the fibre. When Leonard cabled London that there was two miles of asbestos in sight at Yampire Gorge, they cabled him back saying he should take a holiday. Leonard had to send a photograph before it was believed Yampire Gorge contained this much asbestos. Walters and Leonard cleared the way into Yampire gorge by blasting the biggest rocks and pulling them out the way with a camel team. Even after that it took them seven hours to drive their lorry the fifteen miles from the workings to their treatment plant. By 1940, twenty-two men were employed at the Yampire Gorge workings and about 375 tons were mined and transported to the coast (Point Samson) by mule team wagons. During the war communications with England became difficult and de Berrales acquired an interest in the mines. Finally in 1943 the Colonial Sugar Company through its subsidiary, Australian Blue Asbestos Ltd. took over both the Wittenoom and Yampire Mines. Lang Hancock who watched his station property transform to a town stated (1958), “Izzy Walters was the man who stuck it and produced the market that made Wittenoom of today possible. Walter’s partner Len Leonard, put it this way (1958), “But for his (Islwyn Walters) sheer grit and hard work there would be no such thing as Wittenoom. We have him to thank for that.”

Until the Second World War asbestos was mostly imported from South Africa and Canada. The Australian market for asbestos before the Second World War was worth $1 million a year, and there was export potential. Hancock had promising talks with the British, who were desperate to use asbestos as filters in gas masks, and his partners Islwyn (Izzy) Walters and Walter (Len) Leonard had negotiations with Johns Manville in the United States. When the Second World War came asbestos was in high demand for use in tanks, planes, battleships, helmets and gasmasks. In 1943 the mine was sold to CSR Limited subsidiary, Australian Blue Asbestos Pty Ltd (ABA), where Hancock remained as manager until 1948.

In 1946, the Yampire Gorge mine was closed and subsequently Wittenoom Gorge mine was opened in the same year. Production to 1956 is estimated at 590,000 tons of ore from which about 20,000 tons of asbestos were recovered. In 1947 the town of Wittenoom was built to service the nearby asbestos mine. It was built ten kilometres from the mine and mill as there was not a suitable area available to expand the original residential settlement. By 1951 the town had 150 houses and a population of over 500.

In 1948 CSR took over the asbestos project at Wittenoom as the parent company of ABA. From 1950 until the early 1960s Wittenoom was Australia’s only supplier of asbestos with 161,000 tonnes being mined from 1943 to 1966. In an internal report recommending the mine’s closure in 1966, one of CSR’s own executives admitted that “…no thorough investigation of the deposit at Wittenoom was made”. For most of the years CSR mined asbestos, the operation lost money. It struggled into profit for the five years from 1956, and then only by making its workforce work two and even three shifts a day. When the mine closed it had an accumulated debt of around $2.5 million.

In 1944, Mines Inspector Adams reported on the dust menace at Wittenoom and discussed the need to reduce dust levels, and the WA Assistant State Mining Engineer reported on the dangers of the dust being generated at Wittenoom. The first case of asbestosis at Wittenoom occurred in 1946, although it was not conclusively diagnosed until much later. In 1948, Dr Eric Saint, a Government Medical Officer, wrote to the head of the Health Department of Western Australia. He warned of the dust levels in the mine and mill, the lack of extractors and the dangers of asbestos and risk of asbestosis, and advised that the mine would produce the greatest crop of asbestosis the world has seen. He also advised the Wittenoom Mine Management that asbestos is dangerous and that men exposed would contract chest disease inside six months.

Dr Jim McNulty, who was working for the Health Department of WA, provided a first hand account of the work conditions he observed when he visited Wittenoom to do a clinical examination in 1959 (Australian Safety News, May 1995). He reported: “It was generally dirty and dusty, there were clumps of asbestos all over the floor and one’s clothing was rapidly soiled by contact with any surface….. every operation in the mine was associated with dust.” Dr McNulty repeatedly warned the company’s manager of the dangers to the miners and the people living in the town. Dr McNulty and the Health Department did not have the power to order CSR to close down the mine.

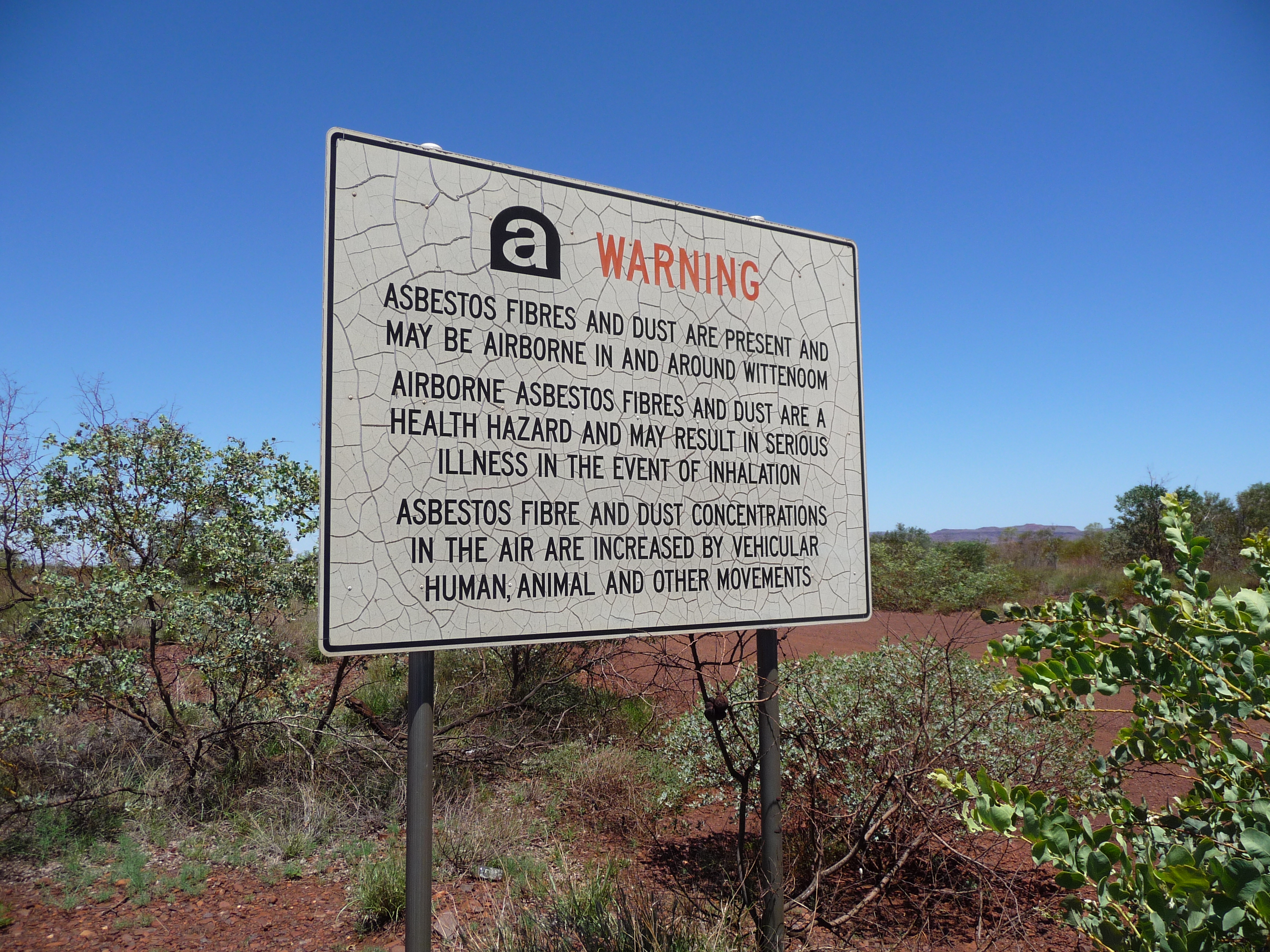

Between 1977 and 1992, eight studies involving air monitoring were carried out by the Health Department of WA and other authorities. There were a number of shortcomings with these studies, which meant the debate over risk to residents was not conclusively settled. Reports by the Environmental Protection Authority provide detail on the extent of the contamination. Inspection reports indicated that asbestos fibres were present in some quantity in almost every area of the town.

In 1978, the State Government adopted a policy of phasing down activity in the town of Wittenoom. This policy was seen as the most appropriate course of action to take in response to the widespread contamination of crocidolite in and around the town. The policy encouraged residents to relocate out of Wittenoom voluntarily, through the purchase of their homes, business and property and included a contribution to their relocation costs. The Shire of Ashburton and many local residents were opposed to closing the town; they lobbied hard to have the town cleaned up and developed as a tourist attraction.

In 1981, the Government re-affirmed its policy for phasing out Wittenoom and initiated planning for a new tourist resort. In 1984, the policy was modified by the Government to ensure that the existing State Government facilities and the Fortescue Hotel would be maintained until alternatives were available. Up until the end of 1991, over $1.4 million was spent under the phasing down policy, with the result that the population of Wittenoom fell from over 90 in May 1984 to about 45 in March 1992. Between 1986 and 1992, around 50 houses and other buildings were demolished by the Government. When the population decreased, the school, nursing post and police station were closed, with alternative services being provided primarily from Tom Price. In 1993 the airport was officially closed and the Government advised the Wittenoom residents that they would not be forced to leave, but new residents would not be encouraged to the town. A number of estimates on the cost and possible methods of rehabilitating Wittenoom and nearby mine sites were produced by organisations such as the Shire of Ashburton, the Department of Minerals and Energy and the Environmental Protection Authority.

In 1993, the Government commissioned CMPS&F Environmental to undertake a feasibility study for cleaning up the town site. The study found there was still extensive contamination, after approximately fifteen years during which attempts were made to clean up the town. The final report proposed a clean up involving removal of 100 mm (3.9 in) of contaminated top soil and replacement by gravel capping under strict guidelines. The cost was estimated at $2.43 million, and the report suggested the town could be developed further after clean up.

A systematic clean up of the town was not undertaken. Members of the Interdepartmental Committee on Wittenoom believed it was unlikely the town could be satisfactorily cleaned up and the benefits of attempting to clean up the town were not in proportion to the costs, or the risks involved. The legal implications of encouraging people to live in a town contaminated with crocidolite (even after clean up) were enormous. If residents or visitors contracted an asbestos related disease at some point in the future, it was very likely they might initiate legal action against the Government or organisations involved in such a project.

As of 2016 Wittennoom had only three permanent residents who defy the Government of Western Australia’s removal of services and stated intention to demolish the town. On 30 June 2006, the Government turned off the power grid to Wittenoom.

A report by consultants GHD Group and Parsons Brinckerhoff in November 2006 evaluated the continuing risks associated with asbestos contamination in the town and surrounding areas and classed the risk to visitors as medium and to residents as extreme.

In December 2006, Minister for the Pilbara and Regional Development Jon Ford announced that Wittenoom’s status as a town would be removed, and in June 2007, he announced that the townsite status was officially removed.

Both the Department of Health and an accredited contaminated sites auditor reviewed the report, with the latter finding that the detected presence of free asbestos fibres in surface soils from sampled locations presented an unacceptable public health risk. The auditor recommended that the former townsite and other impacted areas defined in the report be classified as “Contaminated – Remediation Required”. The Department of Environment and Conservation subsequently classified Wittenoom as a contaminated site under the Contaminated Sites Act 2003 on 28 January 2008.

However, opinion is not unanimous on the danger posed. Mark Nevill, a geologist and former Labor MLC for the Mining and Pastoral district, said in an interview in 2004 that the asbestos levels in the town were below the detection level of most equipment, and the real danger is located in the gorge itself which contains the mine tailings. Residents once operated a camping ground, guesthouse and gem shop for passing tourists. The roof of the gem shop is now caved in and the wood of the guest house is rotten, while the camping ground is nowhere to be found.

It was reported in 2018 that thousands of travellers still visited the ghost town every year as a form of extreme tourism.

The Australian Mesothelioma Registry (AMR) is another way that the Australian government is taking part in the fight against asbestos-related cancer. This national database keeps track of information about people who were diagnosed with mesothelioma after July 2010. It records all new cases in order to help the government develop policies on how to deal with asbestos that still remains in the country and reduce mesothelioma going forward.

The climate in Wittenoom is hot and humid in summer, which made working conditions in the poorly ventilated, dusty mine and mill uncomfortable. Many workers often stayed in the town for short periods only. Although around 200 people were employed at a time, approximately 7,000 workers drifted through the mine in the 23 years of its operation. Nearly half stayed for less than three months. CSR had problems attracting workers to the mine and mill, and in 1951 wrote to the Department of Immigration asking for help. CSR sent representatives to European countries, such as Italy, to recruit workers. Many European immigrants unable to find work in their own country signed a two-year contract with CSR to work at the Wittenoom mine and mill. They were unable to leave Wittenoom before the end of their contract unless they paid back CSR their fare, which for most was impossible.

Working conditions during the operation of the mines and mill at Wittenoom were extremely poor, especially in comparison to those of the 1990s. The biggest problem was the asbestos dust comprising small airborne asbestos fibres. Employees worked continuously amongst the asbestos dust in the poorly ventilated mine and mill, usually without effective personal protective breathing equipment. Safe working practices and systems of work were not evident.

The Australian Blue Asbestos Company employed 6,500 men and 500 women in the mining and milling of crocidolite at Wittenoom between 1943 and 1966. This cohort has been traced periodically for vital status and cause of death since 1975. By 1986 there were 85 deaths from pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma. None occurred within ten years of first exposure to crocidolite. A survey of dustiness in the industry conducted in 1966 has provided a basis for estimates of cumulative crocidolite exposure of the members of the cohort. Exposure-response relationships have been examined. Mesothelioma incidence rates increase exponentially with time since first exposure and also increase with intensity of exposure to crocidolite. Mathematical modelling of the relationship between mesothelioma incidence and intensity of exposure, duration of exposure and time since first exposure results in an estimate of up to 700 cases of mesothelioma in this cohort by the year 2020.

The 1990 Midnight Oil song, “Blue Sky Mine” and its album Blue Sky Mining, was inspired by the town and its mining industry, as were He Fades Away and Blue Murder by Alistair Hulett. The town and its history are also featured in the novel Dirt Music by Tim Winton.

Digital poet Jason Nelson created the work Wittenoom: speculative shell and the cancerous breeze, an interactive exploration of the town’s death. It won the Newcastle Poetry Prize in 2009.

Curated with thanks from Wikipedia